Covid-19, formerly referred to as coronavirus, has already caused a great deal of disruption. But another infection has been running in parallel, often exacerbating the problem: misinformation.

Rumours and deliberate fabrications have spread conspiracies and encouraged some of our worst impulses — already, in the UK, retailers are bracing for supply line interruptions, as people begin panic-buying products. Similar stories elsewhere bring dire (but often false) warnings of stores closing, leading to shortages as people attempt to stockpile necessities.

As one behavioural science expert from the London School of Economics told Wired magazine: “It’s a vicious cycle. You have this over anticipation that things might happen. Because everyone thinks it will happen, they are making it happen.”

But what is the spark for this behaviour? How and why does this fear spread? Simple: the massive, society-wide spread of misinformation is made possible by our always-on, social media-based communications channels. Social media sites and messaging apps have become enormous sources of distortion and fear.

This is not entirely new. In the past the reach of social media and messaging apps have been exploited by unscrupulous actors to spread misinformation that led to protests, violence, and even affected election results.

In the midst of the current pandemic, this same phenomenon is helping to spread false information and strange theories.

Some of these stories offer misleading advice about how to avoid or “cure” the virus (as yet there is no vaccine). Others are more outlandish, such as the claim that Covid-19 is caused by radiation from 5G masts. Either way, this has real repercussions, either by encouraging panic-buying and stockpiling, or by discouraging (or distracting) people from pursuing genuine medical advice.

People reading this may have, for example, seen a post on social media or received a message from a contact (or in a public group chat, which are particularly susceptible to these kinds of thing) that supposedly originated from the board of Stanford Hospital. This is fake, and it is filled with false “tips” on how to combat Covid-19.

Others are using the furore on social media to sell “cures” like silver solutions, or toothpaste that supposedly kills coronavirus. Of course, toothpaste cannot kill viruses. But perhaps these stories can teach us to think about what we uncritically believe, just because it’s said or written in an authoritative way.

We can learn to be more critical of information that muddies the waters of the public sphere — that “common world” that philosopher Hannah Arendt said “gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other.” Let’s not fall over each other.

So what can we do?

It is important, firstly, to consider the source of any information you are reading. If you can’t be sure it is knowledgeable and authoritative, then don’t share it. And if something looks false or misleading, then gently alert the person sharing it. The best thing to do is to show them good information that shows incorrect information for what it is.

- Factcheck.org is a good place to start, or if you want a source that deals specifically with your own country, a list of similar sites can be found on Wikipedia.

- Of course, you can also go straight to an authoritative source yourself: the WHO hosts a page for coronavirus (as it does for all major diseases) complete with tips on how to stay safe and updates on the current situation. They also have a “myth busters” page, addressing some of the most common misinformation about the disease.

- Those using WhatsApp can access their Coronavirus Information Hub which aims to connect people to reliable information about the disease and how to protect oneself from it. Perhaps sensitive to the role apps in this and similar outbreaks of misinformation, WhatsApp are hoping to use their platform to counter the risk of bad information spreading among their users.

- And (if you are one of our enterprise customers) you can also fight bad information with good. Sending out messages that counter misinformation can help prevent unnecessary stockpiling and panic buying, which end up creating very real shortages. For example, letting people know you are still open — or giving advanced warning of changes to opening hours — can reassure them you are there for them. Likewise, let customers know that there are ample stocks of high-demand products, or when new stock will arrive: that way they don’t need to worry about shortages.

The word “pandemic” is concerning. It is important to remain cautious and responsible, but not to panic. To reflect carefully on the information which we read and how we react to it. Misinformation tends to compound already difficult circumstances.

Fortunately, with the tools now available we can counteract it — and we may even learn a thing or two. In the future, we will likely be more thoughtful about what we share online.

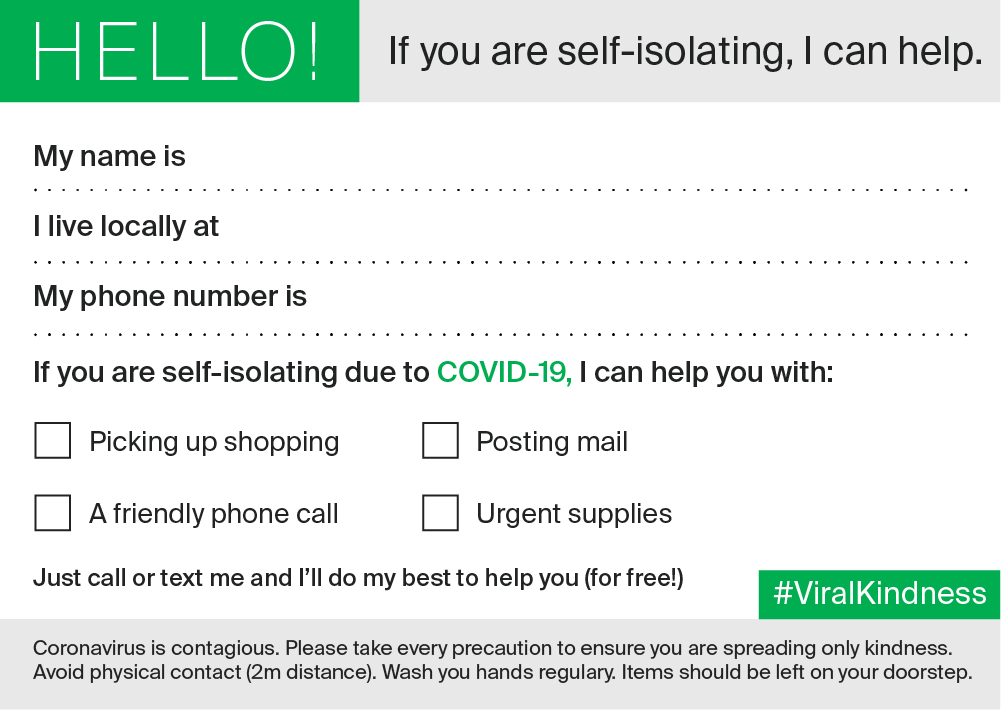

And let’s also not overlook the good stories — of people volunteering to shop for vulnerable people and help those affected by self-isolation. It’s easy to forget that even in the middle of this stressful situation, many people still choose to think about others.

Looked at in this way, our experience with Covid-19 might even make us all better, more considerate citizens.