Online banking has made managing customers’ finances much easier and more convenient. However, an increasing number of cyber-attacks in Ukraine during the past few years, especially against banks, has heightened concerns over the security of institutions and their customers. Cyber-attack isn’t the only thing to worry about either. A very real concern is identity theft and the access it gives to a customer’s account.

As fraudsters and other criminals seek to access and drain users’ accounts, banks worldwide are coming under scrutiny about how they combat these attacks. And for good reason: after all, if a bank cannot properly confirm a customer is who they say they are, then the bank is to blame. How, then, can banks ensure that only customers are able to access their accounts?

By educating their users about the importance of their log-in details, and securing the log-in process with two-factor authentication from GMS.

Passwords and passphrases

Passwords are standard for any login process these days. There are, however, different levels of security with which you should familiarise your customers. Short passwords are easy to guess using two common types of programme. Brute-force attacks are characteristically crude: they try guessing random strings of characters over and over until they find the right one. Dictionary attacks use a list of commonly used words to get there more quickly.

Diligent companies mandate that users should include numbers and symbols to make these attacks harder. However, while they make it harder for the user to remember their own password, they only take slightly longer to break. In fact, dictionary attacks often include commonly used substitutions (0 instead of o, 1 or ! instead of i, and so on) to get around this.

So, a longer password, even if it only uses lower-case letters, is better than using a word you easily remember and adding a few extra characters. There is simply more for a programme to guess. Stringing three to four random words into a passphrase (sometimes called the XKCD scheme, after a comic by ex-NASA engineer Randall Munroe) is ideal. In fact, these may be easier to remember than all those numbers and character substitutions.

Users still aren’t secure

Sadly, passwords and passphrases are a long way from proper cyber-security. This is down to the main problem in any computer system, one that exists somewhere between the keyboard and the chair: people.

People are terrible at maintaining security — they share their passwords, write them down, choose non-random combinations, and, horror of horrors, use the same password across multiple sites. This last problem is very common. That’s why after every data breach at a major website, users are advised to change their passwords for all other sites: the chances are that they have reused the leaked password elsewhere and now all their logins are potentially vulnerable. You should assume your customers are doing the same thing — don’t assume they are safe because you ask for a password.

All these concerns come before we’ve even discussed fraud and phishing — scams designed to harvest a customer’s passwords. These can be as sophisticated as emails containing a link to a site made to look like their real banking site, where they are asked to log in. Cruder scams simply involve someone calling the customer, pretending to be from the bank, and asking for the customer’s password to “confirm their identity.” Surprisingly, this can work. In either case, the fraudster now has the customer’s password and can access their account.

Two-factor authentication

One of the most effective ways of keeping customers and their accounts secure is adding another means of identification on top of the password. But not all methods are equal. Cyber-security writer and journalist Brian Krebs reacted with horror when he realised some American banks were effectively treating usernames as a second authentication factor. Given that many people will reuse their username across sites — or simply use their email, real name, or other easily identifiable information — they are hardly secret, let alone a separate factor.

But what is an “authentication factor?” It’s one of three things: something the user knows, something they have, or something they are. Passwords and usernames are both things the user knows, and both can be guessed. Better security comes from using at least two different factors. Banks actually already know this: they use a form of two-factor authentication when they require customers to use both a card (something they have) and a pin (something they know) to withdraw money from an ATM.

Something most customers have on them, constantly, is a mobile phone. 79% of people do this for at least 22 hours a day. The portability of our phones also makes us more aware of where they are — we keep track of them better and keep them locked more often than our home computers. In fact one mobile-only bank relies on this fact as evidence that mobile banking is inherently secure.

Mobiles can also be locked, using a pin, pattern, or — increasingly — with biometric details like face- or fingerprint-recognition. Assuming a device is lost or stolen, it is still difficult to get into, making it a convenient and secure way to authenticate attempts to access a customer’s account.

How does it work?

Any two-factor authentication (2FA) system works by first having the user present one form or factor of identification, which triggers a prompt to present the second. Only when the second authentication factor has been given will the system give the desired result. For example, inserting a bank card into an ATM will not release any money until the PIN has been entered. Users who opt to use Google’s 2FA system will be prompted to confirm their identity via SMS or an app when logging into their account on a new device.

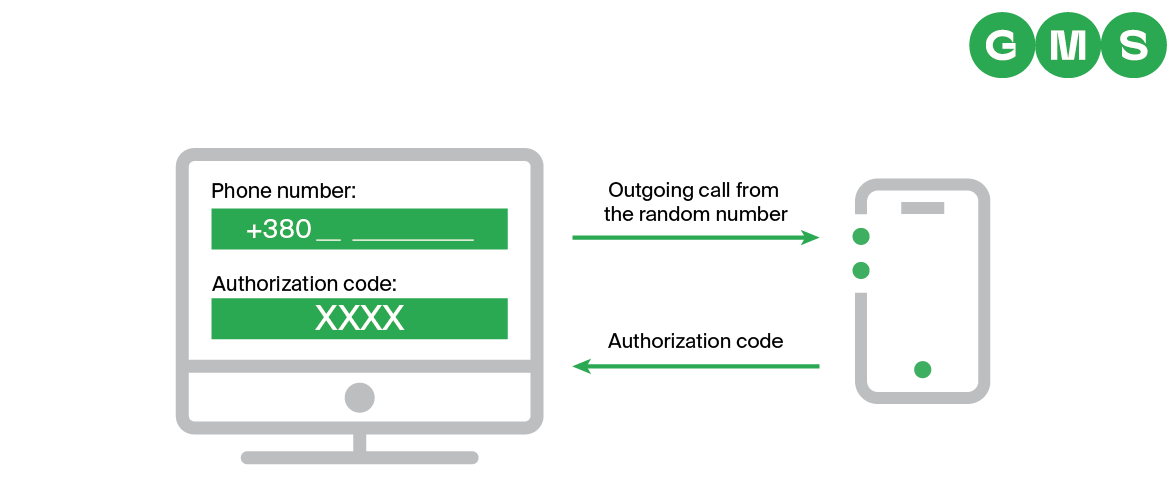

GMS Business Communications Suite works in a similar way to Google’s solutions. However, instead of an SMS with a code in the body of the message — which could be read by a hacker who has accessed the phone remotely — GMS delivers a call to the user. The last four digits (which can be randomly assigned at each call) form the authorisation code the user will be prompted to enter, confirming they have their phone. If the customer is not the person accessing the account they will receive a missed call, alerting them to the attempted intrusion, and stopping the attacker from proceeding any further.

- The customer receives an incoming call from the phone number +38089123 XXXX

- The customer enters the authorisation code, indicated by the numbers replacing XXXX (this can be random or chosen by the bank)

- Access is granted

- As an additional service, GMS can configure IVR authorisation

Implementation is fairly flexible. The most secure model would be to use a 2FA system each time a user logs in. It seems that many US and British banks think this is too difficult to implement and too intrusive for customers just to access balances and statements. Few have implemented proper 2FA, much to the astonishment of the information security community and consumer organisations (who represent the very people the banks believe they are saving from onerous login procedures).

An arguably less intrusive — but unarguably less secure — method would be to require 2FA only for large transactions or transfers, or for the first time a transfer is made to a new account. In either scenario — at first login, or for high-value transactions — 2FA adds a layer of customer protection on top of the password.

As one consumer rights organisation has said: “The best banks… manage to use two-factor authentication without it being too onerous for their customers, so there’s no excuse for others to sacrifice security.” And, as we have shown, GMS’ off-the-shelf solution is easy to deploy and requires no extra hardware — just a customer’s phone number.

Layered security

Keeping banks and their customers secure is a difficult task. There is no single solution or technology that will make an institution totally secure. Banks need a layered approach that addresses internal processes, physical security, and the protection of customer identities. However, as we have seen, even institutions in supposedly well-developed markets, where the best practice principles of cyber-security have been around for a while, lack basic security procedures. In this they lag behind their peers in other industries — even video games take advantage of 2FA to protect their users’ accounts.

Banks would be well advised to keep ahead of the curve, to ensure they are not seen as soft targets and to encourage fraudsters to look elsewhere. In order to help keep customers safe, you should educate them about the importance of a strong password (and encourage them to change it from time to time), and implement a 2FA solution to make doubly sure only they can access their accounts.

At GMS, we provide safe, secure, and reliable 2FA for all of our banking clients. Find out how we can help your bank today.